With stocks in a holding pattern the past few days (where a less negative dealer gamma has stabilized the recent pukeworthy volatility), attention is increasingly turning to corporate bonds, which finally cracked in recent days after remarkable resilience for much of the recent market correction, as well as government Treasuries, where – as everyone knows by know – we have seen some truly stomach churning volatility moves mostly in Europe, where the ECB’s shocking hawkish pivot has led to multi-sigma moves, not just in long-term yields…

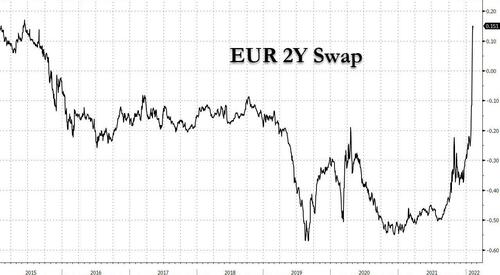

… but in funding conditions…

… while US 10Y Yields are fast approaching the critical 2.00% level, which will likely be taken out as soon as we see a sustained push above 1.95% as noted earlier today.

So how much worse could it get?

While there are multiple views what happens to bond yields next, most to agree that Thursday’s CPI report will be critical in setting at least the near-term trajectory of yields, and as Morgan Stanley’s strategist Matthew Hornbach writes most eloquently, “we think a downside surprise on January US CPI inflation is all that can save government bonds near term” before advising clients that they need “more term premium to protect against higher inflation, hawkish monetary policies” as real rates will rise further, before concluding that “Toto, I have a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.”

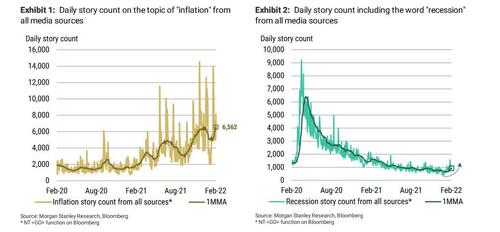

Some more details from Hornbach’s note below, in which he explains why it is still “too early to talk recession” (we disagree, but pro subscribers can read his rationale in the usual place where the full note can be found)..

… and also why it is “Too Early to Buy Government Bonds”:

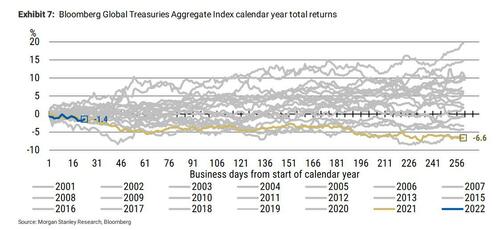

The upcoming US CPI report might be the last hope to save global government bonds from their worst start to the year since 2009 (see Exhibit 7). An upside surprise next Thursday would mean further talk of the Fed raising rates 50bp in March. At a minimum, calls for the Fed to hike at every meeting this year will look much less off-base.

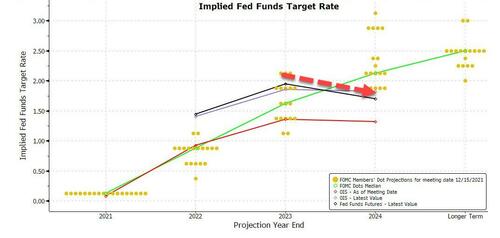

Here Hornbach writes that MS economists continue to call for 4 x 25bp rate hikes from the Fed, “as they still don’t see anything in the data to justify more than 4 hikes and the start of balance sheet normalization.” But as we have noted previously, the consensus is at 5 hikes, and BofA even projects 7 hikes (but does not project a happy ending). Meanwhile, the market prices between 5-6 hikes this year (134bp to be exact, or 9bp more than 5 x 25bp hikes).

With market pricing just 9bp above consensus expectations, Hornbach continues to think markets aren’t pricing enough risk premium for the chance of a more aggressive policy path. “Yes, it’s true that markets didn’t price more than the consensus expected in previous cycles” the rates strategist admits, “but consensus expectations didn’t change as quickly as they are today.”

Going back to Thursday’s CPI, he writes that an upside surprise on January US CPI next week followed by further strength in nonfarm payrolls and even more inflation in February could get expectations of a 50bp hike in March to solidify.

That outcome would certainly jolt expectations for Fed policy this year “and investors aren’t adequately protected against that, given current market prices” according to Hornbach who adds that the same “applies to the pricing of Fed policy in 2023 and 2024, where markets price Fed policy to remain below 2.00%” given:

- The median FOMC participant thinks 2.5% represents neutral policy,

- Chair Powell’s claim earlier this year that policy belongs back at neutral, and

- the median market participant thinks the terminal rate in this cycle is between 2.00- 2.25%;

Looking at market pricing in 2023 and 2024, the rates strategist thinks it incorporates a negative term premium – perhaps reflecting fears of a recession.

Here Hornbach thinks that investors should demand a positive term premium instead.

But where might a negative term premium be justified? According to the MS banker, the answer is: In the very long-end of the yield curve.

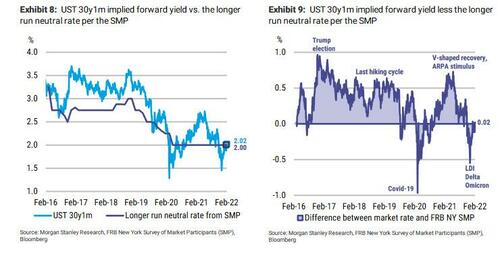

A more aggressive Fed policy path should weigh on longer-dated inflation-risk premiums, as hiking cycles have done in the past. At present, we don’t see much term premium – either positive or negative – in the long end (see Exhibit 8 and Exhibit 9). Still, historical cycles may not be a helpful guide today. The Fed changed its guidance on the policy path (rates and balance sheet) much faster than in the past two cycles. And economic data – first on inflation, and now on the labor market – has been much more volatile relative to expectations. Real term premiums (the bedfellow of inflation risk premiums) should be higher than before, as a result.